Exhibit: Santa Barbara Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage, 1870s-1970s

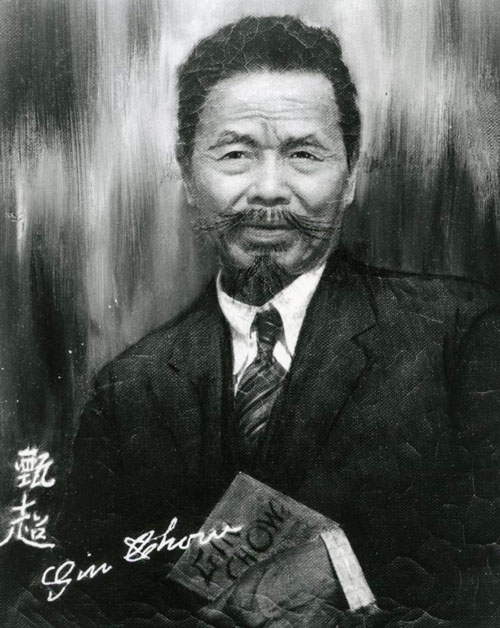

Gin Chow (1857-1933)

The Wonderful Wizard of Lompoc

By Brianna Bruce, Descendant of Gin Chow

Gin Chow

Family History

During the Year of the Fire Snake in 1857, Gin Soo Chow was born on March 19 in Canton, China. He had two brothers (Gin Bow and Gin Yuen) and one sister (May Gin).

Chow’s father (name currently unknown) and paternal grandfather (Gin Hong Yen) are notable for both their influential places in society, as well as the tragedies that befell them due to their prophetic insight. According to Chow, Yen was a wealthy instructor at a prestigious school. Yen’s influence quickly soured, however, when he made predictions that outraged the government, and was imprisoned until his death at 84 years old.

Chow’s father also gained public esteem as a schoolteacher and as the mayor of Choaking City in Canton, but his finances suffered in his fruitless attempts to free Yen. Although Chow’s father appeared to possess psychic abilities, Yen warned him against sharing his visions in order to guide him away from a similar fate.

Immigration to Santa Barbara and Early Work

During his adolescence, Gin Chow sold ducks in order to earn enough money for a steamboat ticket to San Francisco. Chow had saved $31 by his sixteenth birthday, and his father provided the remaining amount.

On March 24th, 1873, Chow and an uncle set sail for California. While it appears that Chow’s uncle remained in San Francisco for an unspecified amount of time, Chow himself stayed there for only two days before joining several of his relatives in Santa Barbara.

Over the next sixteen years, Chow supported himself and nine of his relatives back in China through various jobs. His first significant career prospects took root in 1875, during which Chow began working for Colonel W.W. Hollister and his wife, Annie, at their Glen Annie Ranch in Goleta. He remained there for five years and kindled a lasting friendship with the Hollisters.

Farming

Chow later found employment growing strawberries and various vegetables for Dr. John Cole in Montecito, which inspired Chow to maintain his own garden and sell produce for a living.

In 1897, Chow purchased twenty-two acres of farmland near Goleta, and his farming career prospered to the point that he was later able to upgrade to a thirty-two-acre property in Lompoc.

Marriages and Children

In 1890, Chow’s mother sent him a letter informing him of his engagement to Tom Tim, who lived in China. Chow briefly returned to China, but was unable to bring Tim back to the United States (likely due to the Page Act of 1875, which restricted the immigration of Chinese women to America). Although Tim and Chow produced a son during their short time together, Chow never met his child, and could not return to China to see Tim before she died.

Laura Marjorie Chow Grossi

Roughly a decade later, Chow met Jennie Williams at the Presbyterian Occidental Mission Home for Girls (now the Cameron House). The pair married on December 21, 1903, and had three children who survived into adulthood: Laura Marjorie Chow (1906), Chester Howard Chow (1908), and Pearl Miriam Chow (1911). Their other two children included an unnamed stillborn son (1904); and Clara Chow (1909), who passed away shortly after her birth.

Chow and Williams eventually separated in 1912, with Chow receiving full custody of their children. Williams disappeared with another man, Soo Hoo Wing, and it is unclear whether Chow ever saw her again. Chow and Williams were the first Chinese couple to be granted a final-decree divorce in Santa Barbara County in 1926.

Jennie Williams Chow with her three children: Laura, Chester, and Pearl

Predictions

One of the most memorable aspects of Gin Chow’s life was his ability to predict future events. Although Chow claims in Gin Chow’s First Almanac that he had inherited his ancestral gift of prophecy, he felt unsafe sharing this belief until 1916, which marked the end of a period of massive political upheavals in China. When Chow initially discussed his weather predictions with his Lompoc neighbors, they were quick to dismiss him in favor of official weather reports, and some went so far as to treat him with derision. As his forecasts proved to be generally more accurate than more established sources, however, his neighbors—and, in a few years’ time, newspapers from around the state—took notice. Chow’s generally accurate weather predictions drew avid supporters and vehement critics alike, making him a memorable character in Lompoc. Chow received wider recognition on December 23, 1920, when he posted a list of predictions for the years 1924-1983. Chow notably foresaw two devastating earthquakes: one that would occur in September 1923, and one that would occur on June 29th, 1925. Both claims proved correct, as the Tokyo-Yokohama earthquake of 1923 in Japan ravaged the area on September 1. On June 29, 1925, the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake left 13 dead and at least $8 million dollars of damage in its wake.

Chow’s weather (and general) predictions earned him statewide celebrity. He enjoyed cameos on the KHJ radio station in Los Angeles and in movie newsreels, and also opened as a fortune teller for King Kong’s world premiere on March 24, 1933, at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. He found further success with his two almanacs, Gin Chow’s First Annual Almanac and Gin Chow’s Second Annual Almanac (both published in 1932).

One of Gin Chow’s final predictions involved his death. Although he sustained grave injuries from a bull attack on August 17, 1932, Chow insisted that he would pass on in August of the next year. While he did end up dying in 1933, his time came on June 19 due to internal damage from being hit by a truck, as well as a sudden case of pneumonia.

Gin S. Chow v. City of Santa Barbara

Gin Chow is also known for challenging the municipal water rights of the cities of Santa Barbara and Montecito. Chow grew frustrated at both cities’ water districts due to their diverting of the Santa Ynez River’s surfeit of floodwater to their existing resources, which directly affected the flow of water to his farmland.

In August 1928, Chow filed a lawsuit against Santa Barbara and Montecito. Over the course of the next five years, about forty Lompoc and Santa Ynez farmers joined the case.

Although Chow and his fellow plaintiffs lost the lawsuit on April 3, 1933, the court’s declaration that the districts were entitled to nearly four times as much of the excess water that they regularly accumulated remains a landmark case in terms of riparian rights in California.